How do we manage consent in practice?

-

Due to the Data (Use and Access) Act coming into law on 19 June 2025, this guidance is under review and may be subject to change. The Plans for new and updated guidance page will tell you about which guidance will be updated and when this will happen.

At a glance

- You must obtain consent from the subscriber or user for your use of storage and access technologies. If this involves the processing personal data and you are relying on consent, you must have the consent of the person whose data you are processing.

- How you request consent for your use of storage and access technologies depends on what the technologies do, and to some extent, the relationship you have with your users.

- You must also ensure that you tell your users about any third parties, and that they can access specific information about each one.

- You should consider any implementation of banners, pop-ups, message boxes, header bars or similar techniques carefully, particularly in respect of the implications for the user experience.

- You should make sure that electronic consent requests are not unnecessarily disruptive.

- You must make your consent requests specific to the purpose. This will generally require providing your subscribers and users with granular options about each purpose you want to use storage and access technologies for.

- Neither PECR nor the UK GDPR set a specific time limit on consent. How long your consent lasts will depends on multiple factors.

- If you introduce new storage and access technologies for a different purpose to what you originally stated when consent was granted, you must obtain fresh consent for the new technology or purpose.

- If you use a consent management platform (CMP) provider, you must consider the roles and responsibilities you both have under the UK GDPR.

- You must ensure that any consent mechanism has the technical capability to allow users to withdraw their consent with the same ease that they gave it.

In detail

- When do we need to get consent?

- Who do we need consent from?

- How do we request consent?

- Can we use pop-ups and similar techniques?

- Our expectations for consent mechanisms

- Can we rely on settings-based consent?

- Can we rely on feature-led consent?

- Can we rely on browser settings and other control mechanisms for consent?

- Can we use ‘terms and conditions’ to gain consent?

- Can we bundle consent requests?

- How often do we need to request consent?

- What if our use of storage and access technologies changes?

- How do we keep records of user preferences?

- What if a user withdraws their consent?

When do we need to get consent?

If none of the exceptions apply to your use of storage and access technologies, then you must obtain prior consent.

Who do we need consent from?

PECR states that you must obtain consent from the subscriber or user.

In practice, it can be difficult for you to tell which one provides consent. However, you must ensure one of the parties has provided valid consent.

PECR does not specify whether the user’s or subscriber’s wishes should take precedence if people have different preferences about the use of storage and access technologies.

There are some cases where the subscriber’s preferences may take priority.

Example

An employer (the subscriber) provides an employee (the user) with a device at work, along with access to certain services to carry out a particular task. Completing the task effectively depends on using a service that uses cookies, and a device that accepts them.

In this case it is reasonable for the employer’s wishes to take precedence.

In a domestic context there is usually one subscriber (the person in the household named on the bill) and potentially several other users.

If a user complains that your website is using storage and access technologies without their consent, you may be able to show that you obtained consent previously from the subscriber to demonstrate compliance with PECR.

But, if your use of storage and access technologies involves processing personal data and you are relying on consent, you must have the consent of the person whose data you are processing.

You should ensure information about storage and access technologies, and mechanisms for making choices, are as easily accessible as possible to all users.

Further reading — ICO guidance

How do we request consent?

How you request consent for your use of storage and access technologies depends on:

- what the technologies do; and

- to some extent, the relationship you have with your users.

The key is that you must provide clear and comprehensive information so that your users understand what you want their consent for and what choices they have. You should consider a variety of techniques to achieve this outcome as appropriate for your service.

For their consent to be valid, you must give your users control over all the non-exempt storage and access technologies you use. Any use of a consent mechanism must function as intended to ensure that choices made through the mechanism are respected.

You must also ensure that you tell your users about any third parties and that they can access specific information about each one. It is your choice to decide the most appropriate way to do this in the context of your service. For example, whether it is appropriate to use layers or panels.

For consent to be valid, you must provide the identity of any third parties you share data with. Without this information, subscribers and users cannot determine the consequences of the consent they may give.

If you use a layered approach, you must either:

- provide the identities of third parties on the first layer; or

- be able to demonstrate that the user has access to these identities. For example, on a second layer that you clearly and prominently indicate on the first layer.

Any third party who relies on the consent you obtain from your users must be able to demonstrate that your users understand you intend to share the data with them, and for what purpose.

In general, any consent you obtain in this context is more likely to be valid if you make an active choice to partner with a particular third party for a specific purpose. It may be challenging for you to meet the requirements of valid consent if you use a large number of third parties on your service.

Can we use pop-ups and similar techniques?

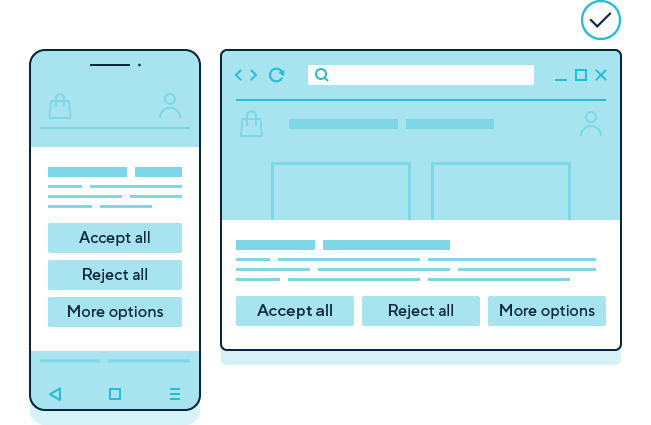

Banners, pop-ups, message boxes, header bars or similar techniques might seem to be the easiest option for you to achieve compliance with PECR — whether that is requesting consent or providing clear and comprehensive information.

However, you should consider their implementation carefully, particularly in respect of the implications for the user experience. For example, a message box designed for display on a desktop or laptop web browser can be hard for the user to read or interact with when using a mobile device. This means any consent from people using a mobile may not be valid as the information may be difficult to access.

Similarly, long lists of checkboxes might seem like a way to make your consent mechanism appropriately granular, but this approach carries different risks. This is because your users may simply not interact with the mechanism or understand the information you’re providing.

You should make sure that electronic consent requests are not unnecessarily disruptive. You should consider how you provide clear and comprehensive information without confusing users or disrupting their experience. However, avoiding disruption does not override the need to ensure that consent requests are valid, so some level of disruption may be necessary.

Many online services routinely use pop-ups to make users aware of changes to the website or to ask for their feedback. You could use this as a way to highlight the storage and technologies you use.

There are challenges with using these techniques. If users do not click on any of the options available and go straight through to another part of your website, you must not use the storage and access technologies that require consent. This is because you must ensure the consent involves a positive action. Silence or inactivity doesn’t qualify. So, you cannot assume that people who don’t engage with your consent mechanism have agreed to the storage and access technologies you want to use.

Our expectations for consent mechanisms

☐ Our consent mechanism makes it as easy to refuse consent as it is to accept.

Description: Consent mechanisms on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right) with equally prominent options to “accept all” or “reject all” non-exempt storage and access technologies, or to customise choices via a “more options” button.

Description: Consent mechanisms on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right) with equally prominent options to “accept all” or “reject all” non-exempt storage and access technologies, or to customise choices via a “more options” button.

Description: Consent mechanisms on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right) with options to “accept all” or to customise choices via a “more options” button. There is no option to “reject all” non-exempt storage and access technologies.

Description: Consent mechanisms on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right) with options to “accept all” or to customise choices via a “more options” button. There is no option to “reject all” non-exempt storage and access technologies.

☐ Our consent mechanism requires a positive action to indicate opt-in from the user, before non-exempt storage and access technologies are set.

☐ Our consent mechanism functions as intended. Storage and access technologies are only set when valid consent is gathered, or when they meet an exception.

Description: Example “more options” tabs of consent mechanisms on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right) with toggles for all non-exempt storage and access technologies turned off by default. A “save and close” button is available to close the mechanism.

Description: The image on the left shows a pop-up consent mechanism on a mobile phone displaying the text: “by continuing to use our website, you consent to our use of technologies that store and/or access information on your device.” There are two buttons beneath it: “ok” and “find out more.” This is an example of pre-enabling storage and access technologies without consent.

The image on the right shows a pop-up consent mechanism on a desktop displaying the text: “By continuing to use our website, you consent to our use of technologies that store and/or access information on your device. To opt out, change your browser settings.” There is one button beneath it which says “ok”. This is an example of pre-enabling storage and access technologies without consent, and relying on a user to adjust their browser settings to opt out.

☐ Our consent mechanism includes granular options for different purposes.

For consent to be valid, you must give your users control over all the non-exempt storage and access technologies you use.

Description: Step 1 shows a pop-up consent mechanism with three equally prominent options for users to “accept non-exempt”, “reject non-exempt” or “customise” the use of storage and access technologies on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right).

Step 2 shows a user selecting the “customise” option and a second layer of the mechanism appearing. This provides specific descriptions for categories appropriate to the service. In this example, there are four purposes: “essential”, “analytics”, “social media tracking” and “advertising.”

There is no toggle for the “essential” category, but there are toggles for the other three categories. The “analytics” category is on by default. The other two categories are off by default. A button displaying “save and close” stores the user’s preferences.

☐ Our consent mechanism informs users about the identities of all third parties their information will be shared with if they grant consent. Users are able to control any information shared with individual third parties.

☐ Our consent mechanism informs users about how they can revisit their preferences.

Description: A graphic displayed on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right). Step 1 displays a webpage with a “settings” icon in the bottom left corner. Step 2 shows a consent mechanism appearing when a user clicks on the “settings” icon. The consent mechanism explains that the “settings” icon allows people to change their preferences at any time. The mechanism can be closed by selecting “save and close.”

☐ Our consent mechanism does not incorrectly use legitimate interests as a lawful basis.

Description: Bad practice examples of consent mechanisms on a mobile phone (left) and desktop (right). The mechanisms have purposes listed alongside separate “legitimate interests” and “consent” toggles. The “legitimate interests” toggles are switched on by default and the consent option toggles are switched off by default. A “save and close” button is available.

Can we rely on settings-based consent?

Some storage and access technologies are deployed when a user makes a choice over a site’s settings. For example, some websites ‘remember’ which version a user wants to access, such as a version of a site in a particular language or what font size to use. These may involve storage and access technologies, such as ‘preference cookies’ or ‘user interface’ cookies.

In practice, it is likely that the use of these technologies falls within the appearance exception and does not require consent.

However, if are using the storage and access technologies for any other purposes beyond the scope of the exception, or if they persist beyond the user’s current session, you must obtain consent.

In this scenario, you could seek consent as part of the process, whereby a user confirms what they want to do or how they want the website to work. For example, by explaining that by allowing their choice to be remembered they are giving their consent in a way that is integrated with the choice the user is already making.

Can we rely on feature-led consent?

In some cases, a user may interact with a feature on your website, such as by choosing to watch an embedded feature or engaging with a chatbot function. At that point, if the user is well informed, it can be considered strictly necessary to provide the service requested by the user.

If this doesn’t apply in your circumstances, you could obtain consent about particular features of your service at the point where the user engages with them. For example, if an embedded video uses storage and access technologies beyond those that are necessary to provide the content requested by the user.

Regardless of whether you requested consent, you must provide clear and comprehensive information because you may process personal data and the UK GDPR will still apply. This includes being clear about when the feature is provided by a third party.

Can we rely on browser settings and other control mechanisms for consent?

PECR states that the controls on an internet browser can be a way in which the subscriber or user may signify their consent.

In a traditional web environment, browsers or similar applications may:

- be set up by their users either to allow or not allow particular storage and access technologies; or

- include certain defaults that prevent their use (eg tracking protection features).

However, you must not assume that each visitor to your online service has either configured their browser in this way, or that they use a browser with these protection features.

For consent to be clearly signified in this way, you must be certain that the subscriber or user has been prompted to consider their current browser settings. This requires evidence of either a positive action that they are happy with the default, or otherwise decided to change the settings.

In the same way that a website may eventually be able to use browser settings as an indication of valid consent, preference settings within a device’s operating system may mature into a consent mechanism for app and web app developers.

But even when browser controls are improved, it is likely not all users will have the most up-to-date browser with the enhanced privacy functionality needed for these settings to constitute an indication of consent.

This means that for now, you must not rely solely on browser settings to indicate consent.

Can we use ‘terms and conditions’ to gain consent?

No. You must ensure that consent is separate from terms and conditions.

You must obtain consent by:

- giving the user specific separate information about what you want them to agree to; and

- providing them with a way to take a positive action to opt-in.

You must not attempt to obtain consent via terms and conditions.

Can we bundle consent requests?

You must keep consent requests specific to the purpose.

Generally, this means you must provide your subscribers and users with granular options related to each purpose you want to use storage and access technologies for.

Example

A firm offers multiple distinct services to users. As part of its account sign-up process, it asks users to provide a single consent to the processing of their personal data for use in personalising the services they receive (such as personalised recommendations and personalised advertising). As well as to set cookies for various purposes, including some not directly related to the personalisation of the account. The user can therefore consent to all the services offered by that company being personalised and cookies being set or refuse consent for all of them.

The user can change the individual consents at a later date in their account settings. However, by presenting the bundled option initially, the company increases the likelihood of users consenting to all processing activities and reduces the chances that they will withdraw that consent at a later time.

This means the consent to set cookies is unlikely to be valid, as it is not specific or informed.

How often do we need to request consent?

Neither PECR nor the UK GDPR set a specific time limit on consent. So, how long consent lasts for your use of storage and access technologies depends on multiple factors. These include:

- the scope of the original consent;

- the expectations of your subscribers and users;

- whether your use of particular storage and access technologies has changed since they last consented;

- how frequently people visit your service; and

- how disruptive consent requests may be for them.

Considering these will help you to decide the appropriate duration of any consent (or rejection) and therefore the point at which you ask your subscribers and users for their consent again.

PECR isn’t intended to inconvenience or unduly disrupt the experience of your users. You should not repeatedly ask or prompt people to specify their preferences as a matter of course. This is particularly the case when someone has refused consent. It is unfair to repeatedly request their consent just because you want them to respond differently.

As a general guideline, we recommend that you request fresh consent for the use of storage and access technologies every six months. If a user has declined consent, you should only choose to seek their consent again after six months.

There may be circumstances where you need to refresh consent more frequently. For example, you must request fresh consent if your purposes or activities change or evolve from what you specified in the original request for consent.

What if our use of storage and access technologies changes?

Your use of storage and access technologies is likely to change over time. For example, you may decide to:

- add or remove particular technologies to your website;

- use existing ones for a new purpose; or

- incorporate new third parties and share information with them.

You must consider how these changes impact on:

- the information you provide to your users;

- any consent you have previously gained; and

- your reliance on any of the exceptions, if applicable.

For example, if you introduce new tags or cookies for a different purpose to what you originally stated when consent was granted, you must obtain fresh consent for the new purpose.

If you embed services or features from other organisations (eg streaming video), you should ensure that you:

- know whether this involves storage and access;

- tell your users about it; and

- are able to configure this feature in the most privacy-preserving way.

Example

A website operator decides to use a consent mechanism that enables the user to:

- consent or refuse non-exempt storage and access technologies; and

- see the names of third parties the website operator shares information with, and for what purposes.

The mechanism stores the user’s choice in a preference cookie for six months. If the user doesn’t visit the site again in that timeframe, the cookie expires.

The website operator adds a new social media plugin to the website. This results in information being collected and disclosed to the social media network.

The website operator recognises that the consent previously obtained does not cover collecting and sharing information with the social media network. It must make sure that consent is specific and informed. It also recognises that this purpose will not be within their user’s expectations.

For this reason, it requests fresh consent from its users.

Further reading — ICO guidance

How do we keep records of user preferences?

You must be able to demonstrate that someone has provided consent. The exact method of doing this is for you to decide as the service provider.

In many cases, service providers use a consent management platform (CMP). The CMP presents information about the storage and access technologies to the user and provides controls for them to make their choice. It can then store records of their consent in digital form.

You could build the CMP yourself. Or, you could partner with a specialist to provide it on your behalf.

However you obtain consent, you must ensure that you appropriately protect any records. A CMP can enable you to accurately record what your users consent to and store this for an appropriate duration.

Many off-the-shelf consent mechanisms also involve preference cookies that are stored in the devices of your subscribers and users. These may have a default expiration period (eg 90 days). As with any other storage and access technologies you use, you should take the time to determine whether this default interval is appropriate. It may seem simpler to use the default option, but you must:

- assess whether it is right for your circumstances;

- take any required actions to change it if necessary; and

- document your decision.

If you do use a CMP provider, you must also consider the roles and responsibilities you both have under the UK GDPR. For example, by determining whether the provider acts on your behalf as a processor, and ensuring that you have an appropriate controller and processor arrangement in place.

What if a user withdraws their consent?

The law says that you must enable your subscribers and users to withdraw their consent at any time. You must therefore ensure that any consent mechanism has the technical capability to allow users to withdraw their consent with the same ease that they gave it. If your mechanism cannot do this, then it does not comply with the UK GDPR’s consent requirements.

You must also provide information about how people can withdraw consent within your consent mechanism, and ensure that any storage and access technologies that have already been set can be removed.

You should make any effects of withdrawing that consent clear.

If someone withdraws their consent to the use of storage and access technologies, you must:

- stop using them;

- cease any processing of personal data the technologies undertake; and

- tell any third parties you are working with that the person has withdrawn their consent.

This is because you cannot rely on another lawful basis for processing, as explained in the section: ‘How does PECR consent fit with the lawful basis requirements of the UK GDPR?’.

You must interpret a withdrawal of consent as a request for erasure and delete any information you hold on the user that you gathered under that consent. Our right to erasure guidance provides more information on how to comply with this request.

Article 19 of the UK GDPR says that you must also notify each recipient the personal data has been disclosed to in reliance on that consent, unless this proves impossible or involves disproportionate effort.

If you are an organisation relying on consent gained by someone else and they inform you that a user has withdrawn that consent, then you must interpret a withdrawal of consent as a request for erasure. You must delete any personal data you hold about that user that you gathered under that consent.

Our detailed consent guidance provides more detail on recording and managing consent.

Example

A user accepted non-exempt storage and access technologies on a travel website when they were looking to go on holiday. They were happy for the travel company to 'remember' their search criteria each time they visited the website, and for this information to be shared with third parties for the purpose of recommending other services to them.

When returning from their holiday, the user no longer wants to be targeted with related adverts, or for their criteria and purchase history to be stored by the website and shared with third parties.

The user clicks a link in their profile to manage their settings and withdraws their consent for the use of non-exempt storage and access technologies.

Through its consent mechanism, the website notifies any third parties it has shared the personal data with about this withdrawal.