Latest updates - last updated 21 March 2024

21 March 2024 - Minor amendments have been made to reflect the fact that section 38 – Health and Safety, is not a prejudice-based exemption.

9 January 2023 - We have clarified the position on the purpose of the neither confirm not deny provisions of the Act, supported with more examples from the IC’s and Tribunal’s decisions. You can find these changes in the sections “What does FOIA say” and “What is the purpose of a neither confirm nor deny response?”.

We have provided more detailed guidance about how to apply the neither confirm nor deny provisions in the Act, supported with more examples from the IC’s and Tribunal’s decisions. You can find these changes in the section “How should we apply the NCND provisions in Part II of FOIA?”.

We have included a new section providing advice on how to deal with requests where the NCND provisions are triggered by information which falls within a certain class. You can find these changes in the section “What should we do if the exemption is triggered by a particular category of information?”

We have included a new section providing advice on how to deal with requests capturing both environmental and non-environmental information. You can find these changes in the section “How should we approach cases where the requested information may include both environmental and non-environmental information?”.

We have included a new section providing advice on how carry out the public interest test in neither confirm nor deny cases. You can find these changes in the section “How should we approach the public interest test?”.

We have provided more detailed guidance on the practical considerations to be mindful of when dealing with requests requiring a neither confirm nor deny response, supported with more examples from the IC’s and Tribunal’s decisions. You can find these changes in the section “What practical considerations should we keep in mind when giving an NCND response?”. This includes clarification of our position on when you can provide a neither confirm nor deny response even though there is already unconfirmed information in the public domain. You can find these changes in the subsection “Information in the public domain”.

We have included a new section providing guidance on issuing a refusal notice in neither confirm nor deny cases. You can find these changes in the section “How do we provide an NCND response to an applicant?”.

About this detailed guidance

This guidance is written for the use by public authorities. It will help you determine in which circumstances you can legitimately refuse to confirm or deny you hold information that an applicant has requested under the Freedom of Information Act (‘FOIA’). Among FoI practitioners, this is called giving a neither confirm nor deny (‘NCND’) response and we use this phrase in this piece. Read this guidance if you have questions not answered in the Guide, or if you need a deeper understanding to help you apply those provisions of FOIA which remove the duty to confirm or deny that information is held.

In detail

- What does FOIA say?

- What is the purpose of a ‘neither confirm nor deny’ (‘NCND’) response?

- How should we apply the NCND provisions in Part II of FOIA?

-

- Confirmation or denial would cause prejudice to the interest the exemption protects

- The exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny is required for the same purpose as the exclusion from the duty to provide the information

- The duty to confirm or deny relates to information which is exempt (or would be, if held)

- Confirmation or denial would disclose exempt information

- What should we do if the exemption is triggered by a particular category of information?

- How should we approach the public interest test?

- How should we approach cases where the requested information may include both environmental and non-environmental information?

- What practical considerations should we keep in mind when giving an NCND response?

- How do we provide an NCND response to an applicant?

What does FOIA say?

Section 2(1)

Where any provision of Part II states that the duty to confirm or deny does not arise in relation to any information, the effect of the provision is that where either —

(a) the provision confers absolute exemption, or

(b) in all circumstances of the case, the public interest in maintaining the exclusion of the duty to confirm or deny outweighs the public interest in disclosing whether the public authority holds the information,

section 1(1)(a) does not apply.

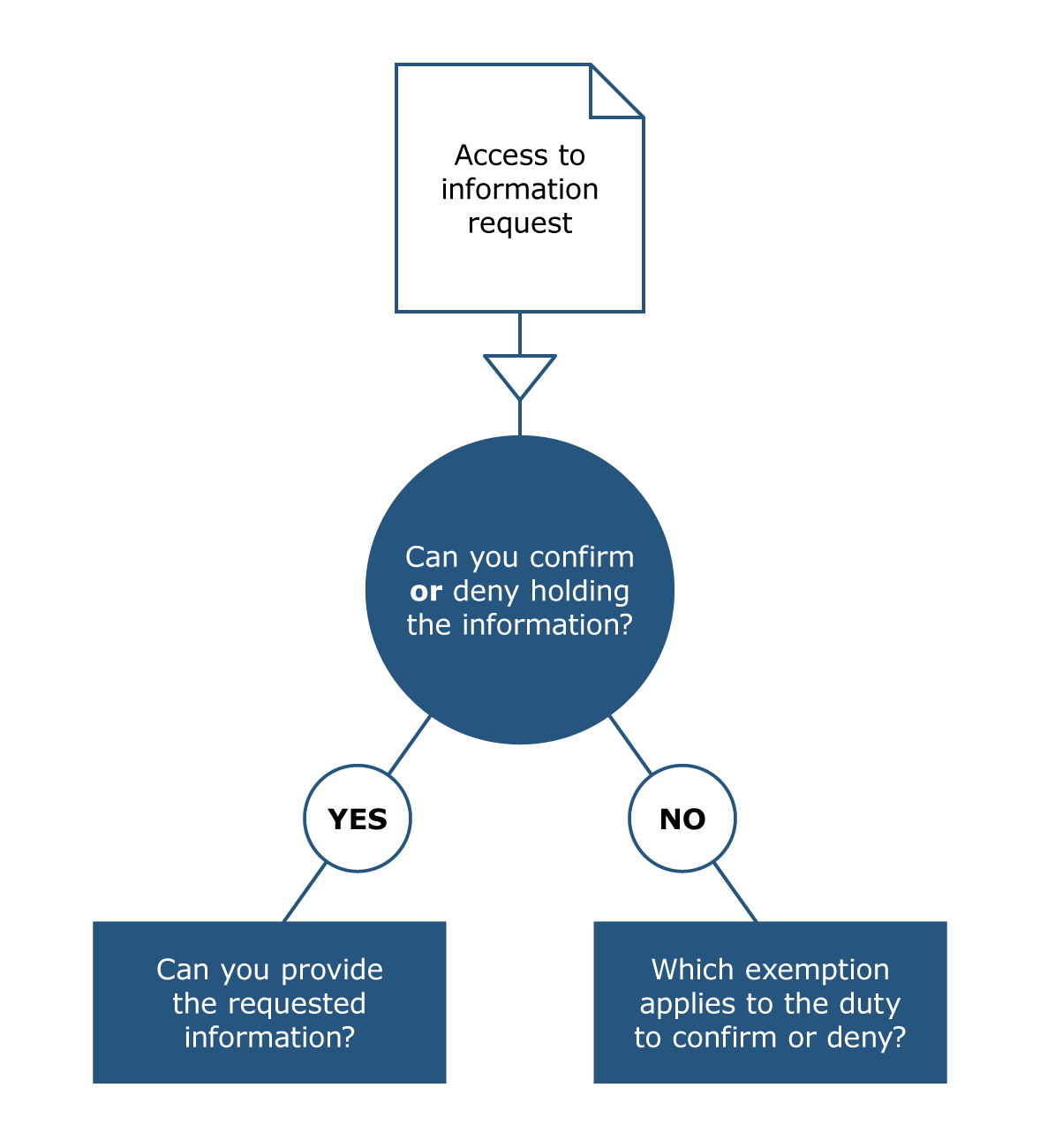

The general right of access under section 1(1) comprises two separate kinds of right to information. Section 1(1)(a) requires you to inform the applicant in writing whether or not you hold the information described in the request. This is called the ‘duty to confirm or deny’. Separate to this, and arising only if the first right applies, section 1(1)(b) requires you to communicate that information to the applicant.

Both rights are qualified and can be disapplied if an exemption is engaged. With the exception of section 21, all exemptions in Part II of FOIA mirror the two-tier structure of the general right of access. That is, they provide for an exemption from the duty to confirm or deny and, separately, for an exemption from the duty to provide the requested information.

Therefore – when dealing with a request for information – you must first consider whether you can confirm holding it or, when an exemption applies to the duty to confirm or deny, whether you can give a so-called neither confirm nor deny (‘NCND’) response. If the exemption you are claiming is qualified, you must conduct the public interest balance to establish if the public interest favours neither confirming nor denying that you hold the information.

In all circumstances, you should carefully consider the effects of confirming or denying whether you hold the information before moving on to consider whether you can provide that information to the applicant.

Example

In Haywood v Information Commissioner (EA/2021/0031P, 22 April 2021), the First-tier Tribunal said that the authority should have responded to the request by applying the neither confirm nor deny exemption of section 40(5A) of FOIA (personal information).

The applicant had submitted a request to the Department for Work and Pension (‘DWP’) about surveillance he said had been carried out on him.

The DWP had originally confirmed holding some information but refused to provide it, stating it was exempt under section 40(1) of FOIA.

At para. 23, the First-tier Tribunal said:

“[t]he DWP should have dealt with this matter under s40(5A) [of] FOIA and neither confirmed nor denied whether it held the information requested, as the fact that the DWP does hold information is in itself a disclosure of the Appellant’s personal information.”

What is the purpose of a ‘neither confirm nor deny’ (‘NCND’) response?

In most cases, you should be able to say whether you hold information relevant to the request. However, there are also cases when confirming or denying information is held can – in itself – disclose information which is exempt or which could prejudice the interest an exemption is there to safeguard.

In these circumstances, the right under section 1(1)(a) is disapplied and FOIA allows you to give a so-called ‘neither confirm nor deny’ (‘NCND’) response. This means that you can respond by refusing to inform the applicant whether or not you hold any information.

The aim of an NCND response is to leave entirely open the position about whether you hold the requested information so that no inferences can be drawn from an acknowledgement of the fact that information is held or not held.

Example

In Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis v Information Commissioner (EA/2010/0008, 23 May 2010), the First-tier Tribunal explained the purpose of an NCND response as follows:

“Part 2 of FOIA provides exemptions from the duty to confirm or deny (s.1(1)(a)) in almost all cases where there is an exemption from the duty to supply information (s.1(1)(b)). The object of such a refusal is, of course, to protect the public authority from the drawing of inferences, whether from a confirmation or a denial, which might cause the same kind of prejudice as disclosure of the exempt information. The fact that exempt information is or is not held may often be a clue as to all or some of its content, or, where such information is protected, its origin. A denial in response to one request will enable a later requester to draw the obvious conclusion, if no denial is then forthcoming” [para. 4].

You can use an NCND response in circumstances where you do not – in fact – hold the information. That is, you can give an NCND response on the basis of theoretical considerations of what would be revealed by a confirmation or denial. This means you do not need to demonstrate the consequences of both confirming and denying you hold the information in order to engage the relevant exemption.

Example

In APPGER v Information Commissioner and FCO (EA/2011/0049-0051, 12 April 2012), the First-tier Tribunal noted:

“It is in the nature of NCND that it covers circumstances in which information is not held, as well as circumstances in which information is held. It can be used to protect sources, and to avoid inferences being drawn from acknowledgement of the fact that certain information is not held. Moreover if NCND could not be used in circumstances in which information was not held, there would be little point in it, as it would then amount to an acknowledgement that information was held” [para. 104].

If you deal with a certain type of information (eg information that relates to a security body), it is also important that you use NCND responses consistently as not doing so could undermine the effectiveness of the exclusion to confirm or deny whether information is held. We will explore this issue in more detail later in the guidance.

How should we apply the NCND provisions in Part II of FOIA?

Using a neither confirm nor deny response depends on the circumstances of the case and the exemption you believe applies to the duty to confirm or deny. You should always carefully consider the type of information that an applicant requested in the context of the relevant circumstances of the case. You should then examine the wording of the exemption you are seeking to claim to establish whether it actually applies.

Generally, the exemptions from the duty to confirm or deny can be divided into four categories on the basis of how the exclusion is phrased. This categorisation is not in the legislation nor in its explanatory notes. However, using the way in which the exclusion is phrased as your starting point might be a useful way to help you think about the different types of exemptions from the duty to confirm or deny and how to apply them to a request. We have summarised these categories in the table below and examine each in the following sections.

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 |

| Confirmation or denial would cause prejudice or endanger the relevant interest | The exemption from the duty to confirm or deny is required for the same purpose as the exemption from the duty to provide the information or to avoid the effects identified in the exemption |

The duty to confirm or deny relates to information that is exempt (or would be, if held) | Confirmation or denial would disclose exempt information |

|

Includes prejudice-based exemptions and section 38: 26(3), |

Includes exemptions such as: 24(2), |

Includes exemptions such as: 22A(2), |

Includes exemptions such as: 22(2), |

1. Confirmation or denial would cause prejudice to the interest the exemption protects

The first category includes circumstances when the duty to confirm or deny triggers an exemption which is prejudice based. This means that you do not need to comply with the duty to confirm or deny under section 1(1)(a) if doing so would, or would be likely to, prejudice or endanger, the particular interest the exemption is there to protect.

The exemptions falling into this category are:

- section 26(3) (defence),

- section 27(4)(a) (international relations),

- section 28(3) (relations within the United Kingdom),

- section 29(2) (the economy),

- section 31(3) (law enforcement),

- sectioned 33(3) (audit functions),

- section 36(3) (prejudice to the effective conduct of public affairs),

- section 38(2) (health and safety), and

- section 43(3) (commercial interests).

If you are relying on a prejudice based exemption to give an NCND response, you must first establish what would be revealed by a confirmation or denial. You then have to demonstrate how confirming or denying that you hold the requested information is likely to cause harm. The test to apply is the same as when you consider the prejudice resulting from the actual provision of the information to the applicant.

In addition to this – if the exemption comprises more than one limb – you also need to explain which limb relating to the duty to provide the information under section 1(1)(b) is relevant to the exclusion of the duty to confirm or deny under section 1(1)(a).

For instance, section 26(3) says that “the duty to confirm or deny does not arise if, or to the extent that, compliance with section 1(1)(a) would, or would be likely to, prejudice any of the matters mentioned in subsection (1)”. The highlighted expression “any of the matters mentioned in subsection (1)” refers to the two limbs of the exemption in subsection 26(1)(a) and (b). This means that – when issuing your response to refuse to confirm or deny – you must explain which of these two limbs is relevant to the exclusion of the duty to confirm or deny under section 26(3).

Example

In Donnie Mackenzie v Information Commissioner (EA/2013/0251, 7 July 2014), the First-tier Tribunal decided that the Information Commissioner’s decision notice had correctly found that the authority was entitled to rely on section 26(3) because confirmation or denial would prejudice the capability effectiveness of British forces (section 26(1)(b)).

The applicant had submitted a request for information to the Ministry of Defence (MoD), asking for a detailed list of technologically advanced weapons the authority might or might not have.

The MoD responded by refusing to confirm or deny whether it held any information by relying on section 26(3).

The Information Commissioner found that the authority had correctly applied the exemption because a confirmation or denial could allow enemy forces to glean information about the capability of British armed forces to identify any potential weaknesses. The Commissioner also found that – although there was a public interest in the public being informed about the potential use of such weapons – the public interest balance strongly favoured maintaining the exclusion of the duty to confirm or deny under section 26(3).

The First-tier Tribunal decided that the decision notice was correct in law. At para. 10, the Tribunal concluded:

“Details of any UK capability in this area or the absence of capability in this area would be of considerable interest to any hostile power and would assist that power in devising counter-measures or give it reassurance that no counter measures were necessary. It would remove uncertainty and assist in the planning or execution of any hostile action. This would therefore prejudice the capability effectiveness and security of British forces.”

The Tribunal also accepted the Commissioner’s findings about the public interest balance.

Although they use a slightly different wording, section 36 (prejudice to the effective conduct of public affairs) and section 38 (health and safety) can also be included in this category of exemptions.

Under section 36 – to be able to rely on the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny by virtue of section 36(3) – you must obtain the reasonable opinion of a qualified person. The opinion must show how confirming or denying that you hold the requested information would result in any of the effects identified by section 36(2). The opinion must also specify which limb of the exemption is relevant to the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny.

Section 38(2) allows you to not confirm or deny you hold the information if doing so would endanger the health and safety of any individual. The word “endanger” does not have the same meaning as “prejudice”. However, for the purpose of the applying the NCND provisions the same approach can be taken with section 38(2) as you would with the prejudice based provisions.

Example

In Decision Notice FS50836455, the Information Commissioner found that the authority was entitled to rely on section 38(2) by virtue of section 38(1)(b) to refuse to confirm or deny holding the requested information. The Commissioner also concluded that the public interest favoured maintaining the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny.

The applicant had submitted a request for information to the Greater London Authority (GLA), asking whether the Mayor of London Sadiq Khan had an official car and the cost of providing it.

The GLA refused to confirm or deny holding the requested information. During the Commissioner’s investigation, the authority further argued that the GLA had a consistent and well-established policy of neither confirming nor denying holding this type of information. This was based on the fact that confirmation or denial could provide valuable intelligence about the Mayor’s travel arrangements. This, in turn, could potentially compromise the effectiveness of the security measures around those arrangements and, consequently, endanger the Mayor’s safety.

At para. 25, the Commissioner decided:

“There is a causal link between confirming whether or not the GLA holds the requested information and harm occurring to the Mayor’s safety. This is because the Commissioner accepts a statement confirming or denying whether the requested information was held is likely to be taken to imply whether or not the Mayor uses a vehicle. Moreover, the Commissioner agrees with the GLA’s argument that any such information would be a potentially valuable piece of intelligence to those looking to harm the Mayor. (…) the Commissioner notes that the threats to the Mayor are clearly ones that are actual and real. In her view, given the potential insight complying with section 1(1)(a) of FOIA would provide to any would be attackers, the Commissioner accepts that the risk of harm occurring is clearly one that is more than hypothetical. Furthermore, the Commissioner agrees with the GLA that it is necessary to adopt a consistent NCND approach given the wording of this request.”

When considering the public interest balance, the Commissioner accepted that there was some public interest in the public authority confirming whether it holds information about the travel arrangements of Sadiq Khan. However, at para. 31, the Commissioner concluded:

“There is a very strong public interest in ensuring the safety of individuals. In the circumstances of this case, given the real and present threat to the safety of the Mayor she is firmly of the view that the balance of the public interest favours maintaining the exemption contained at section 38(2).”

Please see our guidance on Section 38 - Health and Safety for more detailed information.

2. The exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny is required for the same purpose as the exclusion from the duty to provide the information

The second category includes circumstances when the removal of the right of access under section 1(1)(a) [confirmation or denial] is required for the same purpose as the removal of the right of access under section 1(1)(b) [provision of the information] or to avoid the effects identified in the exemption.

The exemptions falling into this category are:

- section 24(2) (national security)

- section 34(2) (parliamentary privilege)

- section 40(5B) (personal information)

- section 41(2) (information provided in confidence)

- section 42(2) (legal professional privilege)

- section 44(2) (prohibition on disclosure).

For example, section 24(2) removes the duty to confirm or deny for the same purpose that section 24(1) removes the right of access to the information, ie for safeguarding national security.

Example

In Decision Notice IC-46074-B721, the Information Commissioner decided that the public authority was entitled to rely on section 24(2) for the purpose of safeguarding national security.

The applicant had submitted a request for information to the Cabinet Office about climate change. The Cabinet Office identified that the information might be held by the National Resilience Capabilities Programme or the National Security Council.

The authority responded by refusing to confirm or deny holding the requested information. It relied on both section 24(2) and its EIR equivalent (reg. 12(6) by virtue of reg. 12(5)(a)).

The Cabinet Office explained that a confirmation or denial that information was held could give rise to inferences being drawn about the level of importance assigned to climate change in the context of the development of the UK’s national security strategy, ie any priority contingency planning in the event of a national emergency. The Cabinet Office argued that this intelligence could prove valuable to ‘hostile actors’ and enable them to “build a picture of potential weaknesses in the UK’s national security strategy. This could put the general public at risk, and also hamper any government response to an emergency.” [para. 23].

The Commissioner accepted the authority’s line of argument as valid and was satisfied that the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny was reasonably necessary for the purpose of safeguarding national security.

The Commissioner also found that the public interest in maintaining the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny outweighed the public interest in confirming information was held. At para. 30–31, the Commissioner argued that:

“Climate change may result in extreme weather events which would have practical negative consequences for the country which may be short or long term. There is a strong public interest in knowing whether this has been considered as a matter of national security as well as, for example, an economic issue. However, the Commissioner recognises that confirmation or denial would create a potential for bad actors to exploit knowledge of the UK’s national security priorities. This is contrary to the public interest such that it outweighs the public interest in providing that confirmation or denial.”

Section 34(2) works in same way as section 24(2).

This category of exemptions includes also circumstances where the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny is required to avoid the effects (eg section 41(2)) or meet the conditions (eg sections 40(5B) and 44(2)) specified in the exemption.

For example, section 44(2) states that the duty to confirm or deny does not arise if compliance with section 1(1)(a) would fall within any of the circumstances outlined in paragraphs (a) to (c) of the exemption.

Example

In Decision Notice IC-50103-M2K3, the Information Commissioner decided that the authority was not entitled to rely on section 44(2) to refuse to confirm or deny holding information relevant to the request.

The applicant had submitted a request for information to the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and asked for copies of correspondence it had sent to a particular company.

Among other exemptions, the FCA relied on section 44(2) and issued an NCND response. The authority identified as the relevant limb of the exemption section 44(1)(a) – ie the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny arose because compliance with section 1(1)(a) would involve a disclosure prohibited under another Act. In this case, the relevant piece of legislation was the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), which the FCA stated prohibits disclosure of information classed as ‘confidential’.

The Commissioner agreed with the FCA that the FSMA was the relevant piece of legislation setting forth a statutory bar on disclosure of certain type of information.

However, at para. 46, the Commissioner explained:

“When determining whether a statutory bar requires a neither confirm nor deny response, the Commissioner is not required to consider what the hypothetical contents of any information that existed might be (if in fact the information existed). Her role is to determine whether the mere act of issuing a confirmation or a denial that information is held would in itself result in the disclosure of information that would engage the statutory bar.”

In this case, the Commissioner found that a confirmation or denial would not reveal anything about the nature of instructions issued by the FCA to the company nor about any information classed as ‘confidential’ which the FCA might have received by a third party [para. 50].

Consequently, the Commissioner decided that the statutory bar was not engaged and the FCA was not entitled to rely on section 44(2) as a result [para. 55].

3. The duty to confirm or deny relates to information which is exempt (or would be, if held)

The third category includes exemptions which state that the duty to confirm or deny does not arise in relation to information that is exempt, or would be if you held it.

Exemptions falling within this category are:

- section 22A(2) (research),

- section 30(3) (investigations and proceedings),

- section 32(3) (court records),

- section 35(3) (formulation of government policy),

- section 37(2) (Communications with Her Majesty and the awarding of honours),

- section 39(2) (environmental information), and

- section 40(5A) (personal information).

For example, section 30(3) states that the duty to confirm or deny does not arise in relation to information which is (or if it were held, would be) exempt information by virtue of subsection 30(1) or 30(2). As we have seen above with other exemptions, if you are relying on section 30, you need to demonstrate which limb of the subsection is relevant to the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny.

Example

In Maurizi v Information Commissioner and the Crown Prosecution Service (EA/2017/0041, 12 December 2017), the First-tier Tribunal decided that the authority was entitled to rely on section 30(3) because – if it were to hold any information relevant to the request – this information was likely to be exempt information by virtue of section 30(1)(c). That is, criminal proceedings the authority has the power to conduct. The Tribunal also decided that the public interest balance lay in maintaining the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny.

The applicant had submitted a request for information to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). The request concerned the case of Julian Assange who was the subject of extradition proceedings conducted by the CPS on behalf of the Swedish Prosecution Authority. At the time, Mr Assange was under the protection of the Ecuadorean embassy in London. The applicant had requested a copy of correspondence on the case between the CPS, the Ecuadorean authorities and the US authorities.

The authority explained that the CPS had a long-standing policy of neither confirming nor denying holding information about extradition proceedings until the person to extradite is arrested. The CPS argued the aim of the policy was to avoid ‘tip-offs’ and “prevent the subject of a request learning about it in advance, and giving them the opportunity to evade justice by leaving the jurisdiction or otherwise seeking to avoid arrest” [para. 77]. The authority also stressed the importance of applying this policy consistently.

The Tribunal accepted the CPS’s arguments and found that section 30(3) was engaged. It concluded that – if the CPS held any information on the case – this would likely be about extradition. At para. 50, the Tribunal noted that “[E]xtradition proceedings are a form of criminal proceedings which the CPS has power to conduct”. Consequently, it found that the CPS was entitled to rely on section 30(3) to refuse to confirm or deny holding information which, if held, would be exempt by virtue of section 30(1)(c).

The Upper Tribunal upheld the decision of the First-tier Tribunal.

4. Confirmation or denial would disclose exempt information

The fourth category includes those exemptions which state that the duty to confirm or deny does not arise when compliance with section 1(1)(a) would – in itself – disclose exempt information.

The exemptions falling within this category are:

- section 22(2) (information intended for future publication);

- 23(5) (information supplied by, or relating to, a security body); and

- 27(4)(b) (international relations).

For example, section 23(5) provides that the duty to confirm or deny does not arise when confirmation or denial would disclose information supplied by, or relating to, one of the security bodies listed in section 23(3). This type of information is exempt under section 23.

Example

In The Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis v Information Commissioner & Rosenbaum ([2021] UKUT 5 AAC, 7 January 2021), the Upper Tribunal (‘UT’) concluded that a confirmation or denial would reveal information ‘relating to’ the Security Service, which is a body listed in section 23(3). As a result, the UT found that the authority was entitled to rely on section 23(5) to refuse to confirm or deny holding any information within scope.

The applicant had submitted a request for information to the Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis (MPS), asking for all information held by the previously named Special Branch about a far-right political party in the years 1974, 1975 and 1983.

In 2006, the functions of the Special Branch had been incorporated within a police unit called Counter Terrorism Command. One of the most important intelligence partners of this unit was the Security Service.

On appeal, the UT decided that the First-tier Tribunal had correctly found that the MPS’ confirmation or denial would reveal information ‘relating to’ the Security Service. As this information is exempt from disclosure, the UT found that section 23(5) was engaged. Therefore, it decided that the MPS was entitled to refuse to confirm or deny holding the information.

What should we do if the exemption is triggered by a particular category of information?

When the exemption is triggered by information which is of a specific description, you must first establish whether the requested information fits into the category of information to which the exemption applies.

For example, in the context of section 40 (personal information), you first need to address the question of whether the information would constitute personal data before moving on to consider whether the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny applies.

Example

In Decision Notice IC-39648-L7Y3, the Information Commissioner decided that the authority was entitled to cite section 40(5B)(a)(i) to refuse to confirm or deny holding the information because doing so would breach the data protection principles.

The applicant had submitted a request for information to the Department for Education (DfE) asking for information about complaints made against Dominic Cummings while he was working as a special adviser in the Department.

In reaching a decision about whether 40(5B)(a)(i) was engaged, the Information Commissioner first considered whether the DfE’s confirmation or denial would reveal any third party’s personal information.

At para. 20, the Commissioner said that to be “satisfied that confirming or denying whether the information is held would result in the disclosure of a third party’s personal data because the request clearly names an identifiable living individual, Dominic Cummings. (…) If the DfE confirmed that it did hold information then that would confirm that Dominic Cummings had been the subject of complaint. If the DfE denied that it held any information falling within scope, that would mean that he had not been the subject of a complaint. Either response reveals personal biographical details and is therefore personal data.”

It was only after addressing this preliminary point that the Commissioner moved on to consider whether providing confirmation or denial would contravene the data protection principles, in line with section 40(5B)(a)(i) of FOIA. In this case, the Commissioner found that the exemption was engaged.

Similarly, in the Rosenbaum example examined above, the Upper Tribunal first looked at whether the information would be information ‘relating to’ a security body before addressing the question of what would be revealed by a confirmation or denial.

This two-step process is helpful when the exemption you are claiming is class-based. All absolute exemptions and some qualified exemptions are class-based. However, as usual, it is important that you consider the wording of the exemption you are claiming in its entirety to establish whether and how it applies to a request.

How should we approach the public interest test?

If the exemption you are relying on is an absolute exemption, you just need to show that the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny applies. For example, in the Rosenbaum case examined above, it was enough for the authority to demonstrate that a confirmation or denial would reveal information ‘relating to’ a security body for section 23(5) to be engaged.

You can find a list of absolute exemptions in section 2(3) of FOIA(3).

However, for qualified exemptions, section 2(1)(b) requires you to carry out the public interest test. This means that, to rely on the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny, you must demonstrate that the public interest in not confirming or denying outweighs the public interest in confirming or denying you hold the requested information.

When you conduct the public interest test in NCND cases, you must assess the public interest balance by reference to your confirmation or denial. At this stage, you should not be considering public interest arguments based on the content of any actual information you might hold.

As explained at the beginning, the general right of access comprises two separate types of right to information: a) the right to know information is held and b) the right to receive the information. Exemptions in Part II of FOIA mirror this division. If you are claiming an exemption on the basis that the duty to confirm or deny applies to a request, the right to receive the information does not arise. Therefore, you must not balance competing public interests based on the consequences of disclosure of the information. Doing so might also put you at risk of revealing whether you hold the information, thereby undermining the purpose and effectiveness of your NCND response.

Example

In Savic v Information Commissioner, Attorney General’s Office and Cabinet Office ([2016] UKUT 535 (AAC), 30 November 2016), the Upper Tribunal (UT) decided that the Cabinet Office was not entitled to rely on section 35(3) to refuse to confirm or deny holding the information. The UT made this finding on the basis that the authority carried out the public interest test incorrectly because it assessed competing public interest arguments by reference to the contents of the information and the consequences of its disclosure.

Building on the First-tier Tribunal’s decision in APPGER, the UT noted [para. 46–47]:

“the test set by section 2(1)(b), which relates to NCND, is significantly different to that set by section 2(2)(b), which arises only when the public authority has confirmed that it holds information and claims that the information requested should not be provided because an exemption that is not an absolute exemption applies (…)

“the statute clearly provides that:

an approach to the public interest arguments on NCND that fails to properly recognise that they are different to those relating to disclosure of the contents of the information of the statutory description in respect of which an NCND response has been given is incorrect.”

In this case, the UT decided that the Cabinet Office introduced an “impermissible contents argument” [para. 70] at the NCND stage. This was because it based the public interest considerations on the effects of disclosing the information and on reliance on the principle of collective responsibility.

At para. 71, the UT concluded that this was impermissible “because both are founded on harm arising from disclosure of the contents of Cabinet discussions and not on simply whether a topic or topics was or was not discussed at Cabinet”.

Consequently, the UT decided that the authority had not applied the public interest test as defined by section 2(1)(b). It found that the Cabinet Office was not entitled to rely on section 35(3) because the public interest in maintaining the NCND exclusion did not outweigh the public interest in disclosing whether the authority held the information.

How should we approach cases where the requested information may include both environmental and non-environmental information?

If you receive a request describing information that might include both environmental and non-environmental information, you might have to consider the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny under both FOIA and the EIR.

This will not always be relevant.

Unlike FOIA, the EIR does not include a separate provision on the right of the applicant to receive confirmation you hold the information. However, there are circumstances in which the EIR allows you to respond by neither confirming nor denying you hold the requested information. The relevant EIR provision is reg. 12(6).

Example

In the Decision Notice IC-46074-B721 examined above, the Information Commissioner noted:

“The information described in the requests could well include both environmental and non-environmental information and therefore, regardless of whether it is actually held or not, the Cabinet Office should consider the requests under both pieces of legislation.” [para. 11]

Therefore, the Commissioner focused the investigation on whether the authority was entitled to refuse to confirm or deny on the basis of the NCND provisions in both FOIA and the EIR, ie section 24(2) and its EIR equivalent reg 12(6) by virtue of reg. 12(5)(a).

What practical considerations should we keep in mind when giving an NCND response?

Applying the exemptions from the duty to confirm or deny can be difficult. Sometimes, you will need to base your NCND response on hypothetical considerations as to whether or not you hold the information. If you do – in fact – hold the requested information, you have to carefully frame your response in a way that does not reveal that you hold it nor gives away its content. When relying on NCND provisions, you should also check whether there is already any official information in the public domain as this would make an NCND response meaningless.

In this part of the guidance, we look at some of the practical considerations you need to be aware of when using an NCND response.

The wording of the request

When considering whether the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny applies, look carefully at the wording of the request. The more specific and narrow its scope, the more likely the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny is engaged.

Requests framed in very general terms are less likely to trigger the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny.

Example

The Financial Services Authority receives a request for information:

“Please send me a copy of all the complaints about banks made to you in the last six months.”

In this situation, it is unlikely that the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny would be engaged. This is because the request’s wording is broad and confirming or denying whether some information falling within this wide category of information is held is unlikely to reveal anything damaging.

“Please send me a copy of all the complaints about branch X of Bank Y made to you in the last month”.

Framed this way, it is more likely that this request triggers the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny. This is because it narrows down the scope of the information requested. This makes it more likely that a confirmation or denial that information is held would prejudice the interest the exemption seeks to protect.

However, if the request is very general but there is an explicit connection between you and the requested information, it might make little sense to give an NCND response.

Example

In the Savic case examined above, the Upper Tribunal noted that, although framed in wide terms, the request was seeking information about a “defined decision” [para. 7] as recorded in Cabinet minutes.

At para. 28–29, the Tribunal commented:

“it seems to us that the terms of the CO Request for Cabinet records, and so expressly of a level of decision-making, for the announced decision to commence a military air campaign has given rise to some of the problems that have arisen in the way in which the NCND response has been advanced in respect of the Cabinet minutes.

“It seems to us that in many cases when reliance is placed on section 35(1)(a) or (b) in respect of a request for information about either (a) a decision that has been announced by a Secretary of State or his Department, or (b) a decision with which a Department has an obvious connection and responsibility, that the connection between the decision and the public authority is such that an initial response of NCND would be unreal and so an NCND argument based on section 35(3) would be rare.”

Information in the public domain

In some cases, if there is already information in the public domain that might reveal you hold the requested information, it might make little sense to give an NCND response. However, this is not always the case. When citing an NCND exemption, there is an important distinction between information in the public domain and official confirmation of that information. Therefore, the fact that some unconfirmed information is known to the public does not prejudice your ability to give an NCND response. If you can demonstrate what an official confirmation or denial would reveal and its consequences, this is enough to engage the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny.

Example

In the Rosenbaum example cited above, the Upper Tribunal concluded that – although there was already information in the public domain – the authority’s official confirmation would allow the public to draw inferences about the Special Branch’s interest in a far-right political party. As a result, the Tribunal decided that the authority was entitled to respond by refusing to confirm or deny holding the information.

The applicant had challenged the authority’s response on the basis that what would be revealed by a confirmation or denial was already in the public domain. The applicant pointed to the existence of a BBC documentary that contained interviews with former Special Branch’s officers about using Security Service agents to infiltrate the party.

The Upper Tribunal rejected this argument. It stated that:

“there is a qualitative difference between credible third party information and official confirmation of that information. (…) The provision of official confirmation by means of a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer that that information was held would provide a qualitatively different foundation for the drawing of inferences from that provided by the unconfirmed information contained in the TV programme.” [para. 57].

Unless the exemption you are claiming is an absolute exemption, you must carry out the public interest test. The fact that there is information in the public domain is a factor you need to take into account when assessing competing public interest arguments.

Be consistent

When you rely on NCND provisions to respond to a request for information of a certain type, you should take a consistent approach on how you deal with these requests. If you receive a series of requests for the same type of information, changing your answer could undermine the aim and effectiveness of your NCND response. This does not mean you can use an NCND response in a blanket fashion. It means identifying the type of information your authority might be asked about which might trigger the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny, and take a consistent approach to responding to requests for that type of information. Being inconsistent when giving an NCND response might give rise to inferences that could have adverse effects or give clues about the content of information that is protected from disclosure.

The most effective way to keep a consistent approach is to have a policy in place to explain to the public when you will give an NCND response on the basis that, in those circumstances, the right to receive confirmation or denial that you hold the information does not apply. This will help you to both manage expectations with applicants as well as to justify your position in the event of a complaint.

Example

In the Maurizi example cited above, the authority had a longstanding policy of neither confirming nor denying holding information about extraditions which it consistently applied over time regardless of whether or not information was, in fact, held or not held.

At para. 84–85, the First-tier Tribunal stated:

“It is plain that the public purposes of the power to bring extradition proceedings would be undermined if there were not a generally consistent NCND policy so as to prevent express or implied tip-offs. In the present context the relevant purpose of the statutory exemption in s30(3) is to enable such a policy to be followed.

“In [the] Manzarpour [case] at [10] it was said: ‘Unless the same answer – neither confirm nor deny (NCND) – is given in every case then an inference will inevitably be drawn by the questioner in a given case from a refusal to answer’”.

On appeal, the Upper Tribunal also endorsed the importance of maintaining a consistent approach when dealing with information requests about extradition.

This case shows how the authority correctly identified the type of information – ie information about extradition – which would trigger the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny under section 30(3). It also identified the rationale for having a consistent approach in dealing with requests about this type of information – ie the power to bring extradition proceedings – to inform its NCND policy when receiving requests for this information.

Giving an NCND response only in relation to some information within scope of a request

On some occasions, you can confirm holding some information within scope of the request while using an NCND response in relation to the other parts of a request for information. You can also confirm holding some information while refusing to confirm or deny holding further information within scope of the same request. This is unlikely to happen often. On those occasions when you consider taking this approach, it is important to look at the request in the round and by taking into account its context as well as your role and functions. This will help you assess the implications of confirming or denying that you hold some information and to minimise the risk of inadvertently revealing something you should not.

Example

In Decision Notice FS50225088, the Information Commissioner found that the authority was correct to confirm it held some information while citing section 35(3) to refuse to confirm or deny holding other information relevant to the request.

The applicant had submitted a request to the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), asking for information about the legal interpretation of the 1949 Marriage Act and of the Human Rights Act. The request was submitted at the time of the impending marriage of the Prince of Wales and Camilla Parker-Bowles.

The MoJ had issued a ministerial statement on the marriage, saying it was lawful for the Prince of Wales and Mrs Parker-Bowles to marry by a civil ceremony. The version of the Ministerial Code existing at the time stated that the Government had to consult the Law Officers before making critical decisions involving legal considerations.

The MoJ responded to the request by confirming it held some information relevant to the request, although it relied on section 42(1) [legal professional privilege] to withhold it. Regarding the provision of the Law Officers’ advice, the authority cited section 35(3) to refuse to confirm or deny holding the information.

The Commissioner found that the MoJ dealt appropriately with the request.

Giving an NCND response without first establishing whether you actually hold the information

As said before, the purpose of an NCND response is to leave the position about whether you hold the information entirely open. This allows you to give an NCND response based on theoretical considerations of what would be revealed by a confirmation or denial and the implications of this. That is, you can consider the consequences of a confirmation or denial by reference to hypothetical information you might hold, but without first establishing whether you actually hold it. When making considerations based on hypothetical information, you need to think about the wording and context of the request and any information you may hold based on your functions and activities. Then, you need to make an assessment based on the wording of the exemption you believe applies.

Example

In the Maurizi case, the Upper Tribunal (UT) decided that the First-tier Tribunal was entitled to find that – were the CPS to hold any information – this would likely be extradition-related correspondence. Based on this, the UT held it was correct to limit the scope of the NCND public interest balancing exercise by reference to this hypothetical information.

The First-tier Tribunal had looked at what correspondence – based on the balance of probabilities – the CPS was likely to hold in light of its ‘proper role’. On appeal, the applicant had challenged this approach and argued that the First-tier Tribunal had applied a flawed hypothesis. In the applicant’s view, this had resulted in a higher likelihood of section 30(3) being engaged.

The Upper Tribunal rejected the applicant’s appeal. In reaching this finding, the UT relied on the oral evidence presented by the CPS. The authority submitted that the only correspondence it was likely to receive from a foreign state would be correspondence about extradition. As a result, the UT concluded that the First-tier Tribunal was right to find that – were any correspondence held by the CPS – this would necessarily be about extradition. The UT also decided that the First-tier Tribunal was correct to find that, based on that supposition, the authority was correct to cite section 30(3) to refuse to confirm or deny holding the information.

How do we provide an NCND response to an applicant?

Section 17(1) requires you to issue a refusal notice to the applicant, including when you respond by refusing to confirm or deny holding the information. Your refusal notice must state that your response is to refuse to confirm or deny holding the information, the exemption(s) you are relying on and why the exclusion from the duty to confirm or deny applies (ie why the exemption is engaged).

If the exemption is a qualified exemption, you must also explain in your refusal notice how you balanced the public interest arguments and why you reached the conclusion that the public interest balance favours maintaining the exemption from the duty to confirm or deny.

You should word your refusal notice carefully to avoid revealing whether you actually hold the information or not or, when you do hold it, revealing its content or its source.

When explaining why the exemption applies exposes you to the risk of revealing whether or not you hold the information, section 17(4) exonerates you from doing so.

Further reading

- Neither confirm nor deny in relation to personal data (section 40(5) and regulation 13(5))

- When can we refuse a request for information? – What exemptions are there?

- International relations defence national security or public safety (regulation 12(5)(a))

- The public interest test

- The prejudice test

- Information in the public domain

- Refusing a request: writing a refusal notice

- How sections 23 and 24 interact – How do we apply section 23(5) and 24(1) of FOIA?

- Section 38: health and safety